Stained Steel

The iron and steel sector is regarded as the core of Indian economy. Its players are big and powerful. It is extremely resource-intensive and polluting. On top of this, it is expanding at a phenomenal rate. This makes the sector a fit case for environmental scrutiny. Delhi non-profit Centre for Science and Environment studied the sector for two years to prepare its environmental profile and rate the performance of its top companies. The exercise undertaken by its Green Rating Project sprang a surprise: the steel sector is struggling to meet even the minimum statutory pollution norms. State pollution control boards do not have the capacity to monitor and regulate these behemoths. What’s worse, the sector is non-transparent and shy of public scrutiny—more than any other sector rated by the project in the past.

The first independent assessment of the steel sector also found it is wasteful in resource use. This is a cause for concern because steel production in the country is likely to increase five times in the next two decades. At this rate, the industry’s energy, water, land and iron ore demand will be immense and unsustainable.

The GREEN RATING TEAM presents a report card, assesses the challenges before the steel industry and suggests a course correction.

.jpg)

Iron ore dust from a steel plant settles on ferns struggling to survive (Photo: Sanjeev Kumar Kanchan)

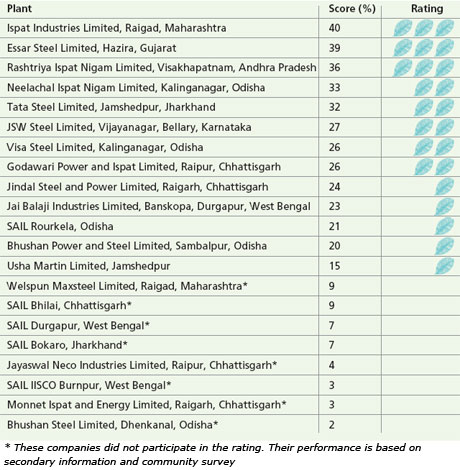

19/100

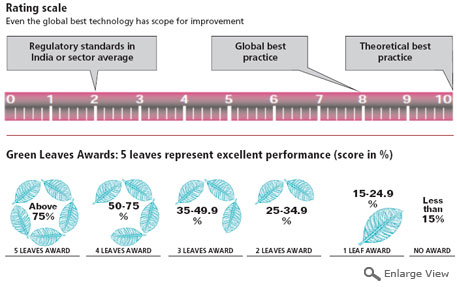

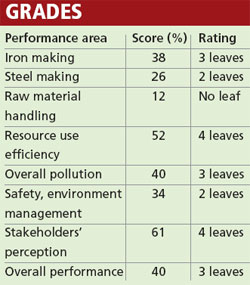

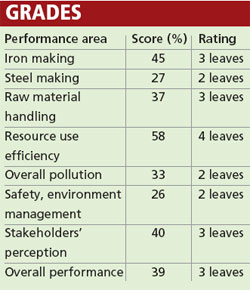

Believe it or not, this is the average score of the iron and steel sector in environmental performance. The highest score is a mediocre 40 per cent and the lowest a dismal 2 per cent.

Not one but eight companies record rock bottom performance of less than 15 per cent. No one qualifies for the top Five Leaves Award or the next Four Leaves. Of the 21 steel plants rated, three fall under the three-leaves category, scoring just above 35 per cent. Five companies get Two Leaves (25-35 per cent), and another five One Leaf (15-25 per cent)

Unlike any other rating

Green Rating Project stands out because of its rigorous, independent assessment and public disclosure

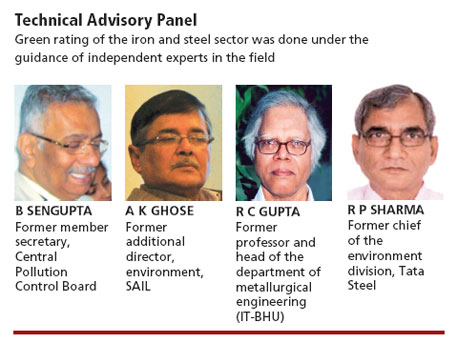

CSE’s Green Rating Project (GRP) is India’s only comprehensive environmental audit system started in the mid-1990s. Unlike other green awards in the country instituted mostly by industry associations, GRP is an independent programme that rates companies after a rigorous process of data collection and verification. The purpose is to inform the public and policy makers, and to nudge industry to reduce its impact on the environment.

Extensive research is the hallmark of GRP. It does not depend on the information provided by companies alone. It gathers data from a range of stakeholders: pollution control boards, communities, NGOs, plant employees, trade unions, media and onsite survey. Most other green awards depend only on desk assessment and consult selected stakeholders. In the GRP process, most of the parameters are verified by production records on the spot and interviews with production personnel. If a company refuses to participate in the rating the GRP team still goes ahead and collects information about it from other sources. The team then crosschecks the data collected and prepares an environmental profile of each company. In the interest of fairness, profiles thus prepared are sent to companies for feedback. It is only after receiving their feedback that the final profiles are prepared. Rating is done on the basis of the final profile.

To make sure the rating is accurate and unbiased, a technical advisory panel oversees the process from step one. The panel of experts not only helps evaluate criteria for assessment but also verifies and fine-tunes all the aspects of rating. It also revisits some plants randomly to crosscheck the results. GRP is free from corporate funding, and therefore, free from conflict of interest. Final ratings, verified and approved by the advisory panel, are released to the public.

GRP encourages all companies to participate. Unlike many other ratings, it identifies not only performers but also laggards in a sector, so that public pressure builds on them to clean up their act.

How iron and steel industry was rated

This is the fifth major industrial sector to be rated by GRP, and it took the team two years to prepare the report. For the rating, GRP selected all the 21 plants that had an annual production capacity of at least half a million tonnes. These plants are producing 68 per cent of the total steel in India. GRP used the life cycle analysis method to assess companies’ performance. Environmental impact of the steel sector happens mostly during raw material sourcing (mining) and production. Since there was no uniformity in the way companies were sourcing raw material—some had captive mines, some bought them from domestic market and some imported them—GRP did not assess the raw material phase. Only production phase from raw material handling till crude steel making was considered to assess companies’ performance.

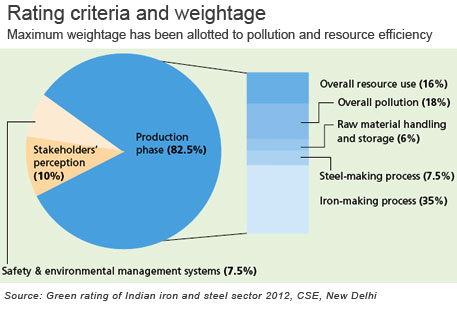

Performance of individual companies and the sector was analysed with reference to global best practices. GRP rated the sector on about 150 parameters which were assigned weightages, depending on their potential environmental impacts (see ‘Rating criteria and weightage’). The maximum weightage was assigned to the iron-making stage—and within that to coke-making and blast furnace process—which is highly polluting and resource-intensive.

Air pollution control, solid waste management and dust emission control from raw material storage and handling areas were given high weightage.

The steel industry’s performance in water, especially water budgeting, conservation measures and reporting, are found poor. Although the per unit water requirement of the industry is low, its overall requirement is high because its production runs into millions of tonnes. In several parts of the country steel plants are causing severe water stress. As a result, water use was given high weightage.

Management systems also received attention in the rating since reporting, transparency and occupational safety performance of Indian steel plants is deplorable. Significant weightage has been assigned to local community perception because it is an alternate tool of assessment. The primary surveyor’s perception and participation of companies have also been given due weightage.

Rating was done on a scale of 10 where the highest score represents theoretical best practices. Even the current best technology did not fetch full marks, as there is scope for improvement. The final scores fetched them Green Leaves Awards (see ‘Green Leaves ...’).

The report card

Steel industry is highly polluting, non-compliant and resource-inefficient

Being environment-friendly should be easy for Indian iron and steel industry because it operates in a favourable market—low costs, high profits and galloping demand. But it is not. The industry is not just careless in managing pollution and resources, but, being big and powerful, it cares little about public opinion. It does not believe in disclosure; it does not welcome scrutiny. This is what the Green Rating Team has found. Of the 21 plants selected for rating, eight refused to give any information. Among them were four plants of mammoth public sector undertaking SAIL.

Stonewalling notwithstanding, every plant was scrutinised on two fronts: pollution and resource-efficiency. Result: even the best steel plants in the country are poor performers when compared to the global best practice.

Environmental Performance

Steel is among the 17 most polluting industrial sectors identified by the Central Pollution Control Board. But this does not mean the industry is extra-careful. On the contrary, almost all the plants the GRP team assessed were found non-compliant with pollution standards in one area or the other. Their contribution to air and water pollution was glaringly high, and their track record in solid waste management abysmally poor.

|

The steel industry releases large amounts of pollutants into the air during all its processes—be it while handling raw material, producing iron and steel or disposing of solid waste.

Blast furnace, by-product coke ovens and sinter plants cause heavy pollution, but the heaviest is from coal-based sponge iron plants. The main pollutants are particulate matter, oxides of sulphur and nitrogen and carbon monoxide. What’s worse, India is the largest producer of coal-based sponge iron. Companies prefer not to use pollution control equipment in these plants because running them requires a lot of energy. Many of them release untreated air through the roof instead of the chimney, where pollution is regulated.

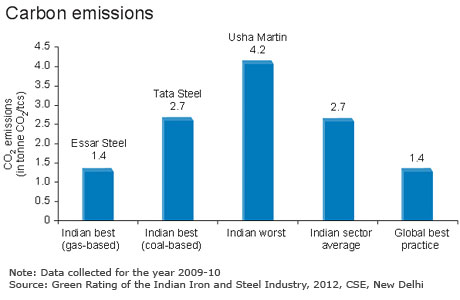

The industry uses a lot of energy. Therefore, its CO2 emissions are high. On an average, primary steel plants emit three tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel. The global best is 1.4 tonnes of CO2 per tonne of steel. The Indian average is pulled down by the growing emissions from coal-based sponge iron plants. If the trend continues, by 2030 Indian steel sector will emit about 800 million tonnes of CO2—about half the current greenhouse gas emissions of the country.

These emissions are hazardous like the thick layer of red dust that covers Kerala Samajam School in Jamshepdur. Its students complain of eye irritation and breathing problems. The red dust comes from the waste hot slag that Tata Steel dumps on the plant’s premises.

In a similar case, students of a government school near Godawari Power and Ispat Limited (GPIL) in Raipur are affected by heavy dust emissions. The plant dumps an amalgamation of sponge iron and char from a height to separate them. In the process dust gets airborne.

For people living close to steel plants black and red dust is common. But the regulatory authorities are nonchalant. Their monitoring is poor and enforcement poorer. No plant meets ambient air quality norms. Efforts to reduce emissions, especially fugitive emissions from raw material handling and storage, are minuscule.

Slag disposal is a major environmental problem with steel making. For the past 15 years, Jindal Steel Plant Limited (JSPL) in Raigarh has been dumping slag from its steel melting shop (SMS) and waste from its sponge iron units at its dump site five km from the plant. During rainy season, pollutants from the site reach Parsada village. At the receiving end are farmers whose crops are suffering.

On an average, for every tonne of steel produced companies dump half a tonne of solid waste. In 2010-11, 35-40 million tonnes of solid waste was dumped on land for the 70 million tonnes of steel the country produced. This is a high cost to pay for steel.

Globally, the best practice is to dispose of less than 100 kg of solid waste for one tonne of steel produced. This waste is largely from the plant’s SMS, where the iron extracted from ore is converted into steel. Solid waste comprises metal oxides, silica and heavy metals. Companies across the world use this waste to build roads and railway tracks.

India, too, can use almost all the solid waste generated from its iron and steel plants. Blast furnace slag can be used to manufacture cement; metals can be recovered from SMS slag and reused; char from sponge iron plants can be burnt to produce energy; and the remaining slag can be used in construction works.

As the industry races to expand, it faces the big challenge of disposing of the bulk of waste it will generate. The Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Limited (RINL) in Visakhapatnam, a coal-based integrated steel plant with captive power plant, generates 0.24 tonnes of waste for one tonne of steel.

At present, it annually disposes of about 0.72 million tonnes of solid waste for producing three million tonnes of steel. By the next decade, the plant aims to produce 10 million tonnes. If it does not use its waste, then after expansion the plant will have 2.4 million tonnes of solid waste to manage.

RINL has 9,000 ha in which it can dump its waste. But not many plants have so much land. Tata Steel produces 0.21 tonnes of solid waste for every tonne of steel. The 10-million tonne plant produces 2 million tonnes of waste every year. The land at its disposal is limited. So it dumps waste outside the plant’s premises near river banks, causing pollution and problems for the community.

Coal-based sponge iron plants generate more waste than the steel they produce. JSPL, for instance, generates 1.2 tonnes of solid waste for each tonne of steel production. The Union Ministry of Environment and Forests (MoEF) has failed to crack the whip on companies. In fact, it has been easy on them by not setting proper conditions for solid waste disposal. The conditions simply say that plants must recycle waste and should not create air and water pollution. MoEF overlooks all non-compliances and blindly provides clearances accepting the industry’s assurance that it will reuse all waste “gainfully”.

Water pollution

The industry rarely reuses its waste water. RINL, for instance, releases its metallurgical effluent into the sea. In fact, the plant releases more effluents at night when monitoring is difficult. Fishers are harried by the dark brown effluent that is killing fish. When the Andhra Pradesh Pollution Control Board failed to act, people approached the human rights commission. The problem has been persisting for the last two decades.

As per the global best practice, plants should not release wastewater at all. They should recycle and reuse their effluents. But in India, the average effluent discharged from integrated BF-BOF (blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace) alone is about 1.75 m3 per tonne of crude steel (tcs).

Plants that use the BF-BOF process and by-product recovery coke ovens pollute the most. Gas and coal-based sponge iron plants have relatively little wastewater discharge. Effluents from by-product recovery coke ovens are highly toxic because they contain cyanide, phenol and other organic and inorganic toxic chemicals. None of the by-product recovery coke ovens GRP assessed met norms for cyanide and phenol.

Companies have found a clever way of bypassing the issue of pollution. During coke quenching, a process in which water is used to cool burning coke, plants use the polluted effluents. This way they “use” their polluted water and gain brownie points from the monitoring agency. But they are actually converting water pollution to air pollution. There is no regulation to control toxic air pollutants from coke quenching.

| Offence at every step

Defying norms is the norm in the steel industry

Blast furnace and coal-based sponge iron plants are the most polluting routes in steel making.

In large integrated steel plants with blast furnace technology coke oven is the main source of air emissions. Its batteries leak benzene which puts workers’ health at risk.

While all plants claim compliance with leakage emission norms, only 25 per cent of the batteries were found complying with the standards during the Green Rating Project (GRP) survey. Among the non-compliant ones were SAIL plants of Bhilai, Bokaro and Durgapur, and Tata Steel. In iron ore preparation stage called sintering many plants were found not meeting stack emission norms.

In the subsequent stage of liquid iron making in blast furnace, a huge amount of fugitive emissions occur. Most of the plants have not bothered to install proper dust capture system they had committed years ago.

Similar problems were observed in water pollution. SAIL Bhilai claims it meets all coke oven effluent norms. But it was found that the pollution control board does not even monitor concerned parameters like cyanide, phenol and ammonical nitrogen.

Meanwhile, people of the villages nearby claim that a large quantity of tar sludge flows from the drains.

Plants also claim that due to poor quality of raw material the waste cannot be reused. The gas cleaning plant of SAIL Rourkela’s blast furnace was polluting the Brahmani river thus.

Fugitive emissions are not arrested despite the presence of suitable technologies, as was found in coal-based sponge iron plants.

The Union Ministry of Environment and Forests introduced new norms to control emissions, but no company were found adhering to them.

Gas-based sponge iron plants are also not that clean. Their raw material handling areas had high dust emissions leading to poor quality of ambient air.

|

Resource Efficiency

The iron and steel industry is a voracious consumer of the natural resources: iron ore, coal, water and land. To produce 70 million tonnes of steel in 2010-11, the industry consumed about 60 million tonnes of coking coal equivalent, 111 million tonnes of iron and 700 million tonnes of water. It could have done with much less.

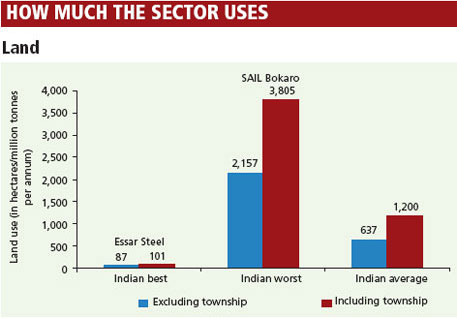

Land requirement

In many cases, the steel industry has got as much land as it wants but does not need. The industry justified its demand by saying it was for future expansion or for building townships.

Public sector companies occupy maximum land. SAIL Bokaro, for instance, occupies a vast area of 14,000 ha for its production of 4.5 million tonnes of steel. RINL follows with 9,000 ha for 3 million tonnes of steel and plans to double production in the next 20 years. The newly installed, state-owned Neelachal Steel in Kalinganagar, Odisha, controls 1,000 ha with an installed capacity of just one million tonnes of steel.

Still, the companies act miserly when they have to compensate or rehabilitate people. Between 1998 and 2002, Bhushan Power and Steel Limited (BPSL), Sambalpur, acquired large tracts of fertile land from the people of Thelkoloi, Dubanchapal and Khadiapali villages. The company gave them asbestos roofed 35 square metre houses and paid just Rs 3.5 lakh per ha.

The 21 companies that GRP rated have 60,000 ha to produce 51 million tonnes of steel. This means, an average of 1,100 ha for every million tonne of steel.

Considering the sector’s future expansion plan, it will need an additional 0.33 million ha—five times the size of Mumbai. Where will the additional land for expansion come from?

The best practice in land use is 200 ha per million tonne of the installed capacity. This includes land for production plant, power generation, waste disposal and staff colonies. If all plants were to use land as efficiently as the best practice, then 60,000 ha currently held by all large plants can produce up to 275 million tonnes of steel. This also means that the steel industry need not acquire land for many years to come.

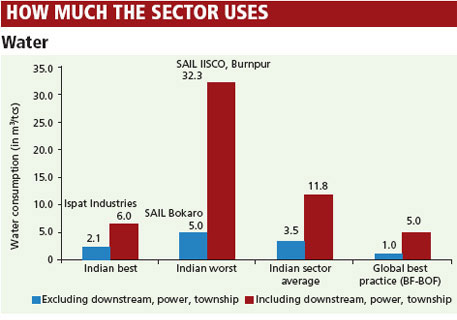

Water consumption

Given the scale and pace at which the steel industry is growing, water use in the industry is set to become a big problem. But the industry is not bothered.

As part of its expansion plan, JSPL constructed a check dam on the Kelo river in 1998. Ever since, Gudgahan village in Raigarh faces acute water crisis. People of Gudgahan depend on the Kelo for their daily needs. The village has no other waterbody. The crisis, therefore, deepens during summer months. JSPL has taken no corrective step.

At present, Indian steel industry consumes on an average 3.5 m3 of water to produce one tonne of crude steel. This much without taking into account the water consumed in two major areas—power generation and townships.

SAIL Rourkela, for instance, consumes 4 m3/tcs of water in its plants. When water consumption in its power plant and township is included, its total water use jumps to 27 m3/tcs.

Tata Steel, which uses 5.7 m3/tcs, withdraws 57 million m3 of water every year just to meet the production process requirement of its 10 million-tonne plant. This much water can meet the daily requirement of 1.6 million people, more than the population of Jamshedpur, where Tata Steel is based.

Two of the most water-inefficient plants, SAIL Bokaro and SAIL Bhilai, use 80-85 million m3 per year each to produce 4.5 million tonnes of steel. Both have massive expansion plans.

The BF-BOF plant consumes maximum water: an average of 4 m3/tcs. The global best practice is 1 m3/tcs.

Yet, there is no push to improve. The only benchmark for water use is an archaic and ambiguous voluntary standard that MoEF had set in 2003 under corporate responsibility for environment protection programme (CREP). Plants deliberately under-report water use to show compliance with the MoEF standard.

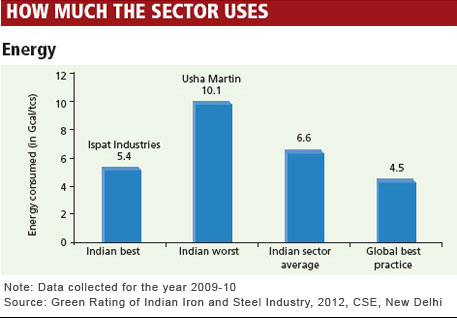

Energy consumption

Over the years, the industry has reduced its energy consumption. But there is a definite downslide in the recent years because the industry is moving towards producing steel from the energy-inefficient, coal-based sponge iron technology.

The Indian average in energy consumption is 7 giga calories (GCal)/tcs. The global best practice is 4.5 GCal/tcs. The most energy-efficient plant in India, Ispat Industries, Dolvi, uses 5.4 GCal/tcs. The worst is Usha Martin, a coal-based sponge iron plant, which uses 10 GCal/tcs. Coal-based sponge iron process is the most energy intensive using 8.5-9 GCal/tcs. This process gains from being inefficient.

It consumes more energy than required for making sponge iron, and the waste heat released is used for power generation. These plants dubiously attain clean development mechanism (CDM) credits by claiming that such projects save energy.

Occupational Health, Safety

Most of the companies that GRP rated had occupational health and safety management system certifications (OHSAS 18001). But their performance, to say the least, was poor. They had high fatalities. At least 63 people died between 2007 and 2010 in the OHSAS 18001-certified plants. Most of them were contract workers. JSPL, Raigarh, had 13 fatalities in these three years.

The industry does not undertake critical health tests for its workers, like those for cancer-causing chemical exposure and heat stress. Health records are poorly documented and never disclosed.

Almost half of the workforce is on contract. These workers are usually employed in dangerous areas of the plant with minimal health and safety protection. SAIL, for example, employs contract workers in the blast furnace of its Durgapur plant to remove blazing hot material that obstruct the blast furnace’s operations. This is dangerous considering the temperature of the blast furnace can be as high as 1,600°C. Many accidents have occurred with contract workers while performing such activities, says one such worker. But the industry remains oblivious to such safety concerns.

India’s best

Even the highest-scoring steel companies are far behind the global best

Average. That’s how India’s three best iron and steel plants have performed. With just Three Leaves in their kitty, Ispat Industries, Essar Steel and Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Limited (RINL) have a long way to go to be certified truly green companies.

ISPAT INDUSTRIES, DOLVI

The 3.6-million-tonne per annum (MTPA) integrated plant spreads across 490 hectares (ha) near Dolvi village in Maharashtra’s Raigad district. It uses two processes to produce iron—natural gas-based plant of 1.6 MTPA capacity to produce sponge iron, and blast furnace of 2 MTPA capacity to make hot metal. Both sponge iron and hot metal are fed into an electric arc furnace to make steel.

During its survey, GRP found the company to be most transparent. Its gas module is one of the largest and most efficient in the country. The blast furnace has advanced technologies like pulverised coal injection and top pressure recovery turbine. It is also India’s only plant that uses energy-efficient thin slab casting technology.

The plant consumes 5.4 Giga calories (GCal) of energy per tonne of crude steel (tcs). This is the lowest in India but about 20 per cent more than the global best. Its blast furnace consumes the lowest in India—395 kg of coke per tonne of hot metal (tHM). The global best practice is 250 kg/tHM. Thermal energy consumption in the gas sponge iron plant is 2.6 GCal/tonne sponge iron against the global best of 2.25 GCal/tonne. Carbon emissions from Ispat Industries during the production process are 2 tonne CO2 per tonne of crude steel (tcs). This is about 40 per cent higher than the global best practice.

One of the most land-efficient plants, Ispat Industries occupies about 140 ha per million tonnes of steel capacity. It annually draws 7.4 million m3 of fresh water from Nagothane dam on the Amba river, about 20 km from the plant. It consumes 2.1 m3/tcs water in its production process, the lowest in the country. It discharges very little wastewater. But the little that it does flows into Dharamtar creek. This is poorly monitored.

The plant disposes of about 0.23 tonnes of solid waste per tonne of crude steel. This is one of the lowest in India but almost double the global best practice. The blast furnace slag is sold to Indorama Cement. The plant’s steel melting slag is given to an external agency to recover metal. Waste from other areas is used in the sinter plant. However, the company was not able to clarify how it disposed of nickel catalyst, a hazardous waste, from the sponge iron plant.

The problem with the plant is poor management and handling of gas cleaning plant sludge. It is struggling to meet ambient air quality norms in many areas. Fugitive emissions were found high from solid waste dumping areas, product separation areas and from raw material storage and handling. Air pollution from its steel melting shop (SMS) was found too high. Monitoring of ambient air quality and stack emissions was also inadequate.

On the health and safety management front, the plant has a poor track record. As many as nine fatalities were reported during the three years that GRP assessed. Of the entire plant, only its gas sponge iron operation is certified ISO 14001. The environment department was found lacking in initiatives and the green belt development around the plant was poor.

While Ispat Industries provides employment and drinking water to 44 villages, the plant’s transport activity has irked many. Transportation of material through ships affects fishing. In fact, the company had to pay compensation to fishers for damaging fishing nets and boats.

ESSAR STEEL, HAZIRA

Spread across 300 ha in Hazira, in Gujarat’s Surat district, the plant has a production capacity of 4.6 MTPA of crude steel. It is expanding to produce 10 MTPA. But the expansion will be through coal-based steel-making processes like Corex and blast furnace because gas is not available cheap. This means the plant’s overall environmental performance will deteriorate in future.

Essar Steel is India’s only fully operating gas-based integrated steel plant. The plant produces sponge iron through a gas-based process. It has five sponge iron modules with a cumulative capacity of 5 MTPA. Its four electric arc furnaces have a cumulative steel capacity of 4.6 MTPA. At Visakhapatnam, it has a pellet plant of 8 MTPA capacity, which makes pellets from iron ore. These are transported by ships to Hazira where they are used for making sponge iron. One of the plant’s five sponge iron-making units, of 1.6 MTPA capacity, is among the largest in the country.

Essar Steel has installed some advanced technologies to become energy-efficient. It puts hot sponge iron directly into the electric arc furnace, reducing energy consumption by 20 per cent. Eighty per cent of the material that it uses to make sponge iron is pellet. This further reduces energy consumption. Presently, the plant is installing a system to collect exhaust gases from its four older sponge iron modules to generate 19 MW power. This will control air pollution and assist in energy efficiency.

Essar Steel consumes 5.5 Gcal/tcs energy, the second lowest in the country after Ispat Industries. Its specific thermal energy consumption in sponge iron plant is 2.6 GCal per tonne of sponge iron against the global best practice of 2.25 GCal per tonne.

Since it is a natural gas-based plant, the plant’s specific carbon dioxide intensity is the lowest, at 1.4 tonne CO2 (tCO2)/tcs. This is equal to the global best practice. Essar Steel is the country’s most land-efficient plant. It occupies about 65 ha per million tonnes of steel capacity. However, it is inefficient in water management. The plant annually draws about 16 million m3 of fresh water from the Tapi river. This will increase considerably when the plant starts its 5-MTPA, coal-based iron-making plant. Its current water consumption is 2.7 m3/tcs, more than double the global best practice. The plant discharges a low 3,000 m3 per day wastewater into the Tapi river estuary. Ideally, it should recycle and reuse all its wastewater. It disposes of about 0.27 tonne of solid waste per tonne of crude steel. This is mostly the steel-making slag. The company uses some of it to fill low-lying areas and sends the remaining slag to its Visakhapatnam pellet plant for reuse. It recently started using slag in tile-making and construction work.

The plant’s emissions through chimneys were within the norms. Its air pollution monitoring was also satisfactory. But two major pollution issues are high fugitive dust in raw material handling and storage areas, and high fugitive emissions in steel melting shop.

Another area of concern is occupational health and safety. Despite an OHSAS 18001 certification, its safety record is below par. Between 2007 and 2010, seven workers died in accidents inside the plant.

Its environment management system is in place and has an ISO 14001 certification, but the plant’s green belt development is inadequate. The pollution control board is perturbed because the plant was undertaking expansion plans without the requisite Coastal Regulation Zone clearance. Overall, the plant received an average rating for transparency under GRP.

RINL, VISAKHAPATNAM

Rashtriya Ispat Nigam Limited (RINL) is spread over 8,888 ha in Visakhapatnam district of Andhra Pradesh. Its installed capacity is 3 MTPA of crude steel. It uses the blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) route. It has four by-product coke oven batteries of 2.7 MTPA coke production capacity, two sinter machines of total 5.25 MTPA capacity, two blast furnaces of total 3.2 MTPA hot metal production capacity and three basic oxygen furnace of total 3.0 MTPA steel capacity.

The plant has installed coke dry quenching which reduces pollution from coke ovens and minimises water consumption. Its blast furnaces are equipped with top pressure recovery turbines which use waste energy from blast furnace to produce electricity. It recycles sewage from the township to use it for cooling purposes in the plant.

RINL’s energy consumption and carbon emissions are comparable to the sector’s average. Its per unit energy consumption is 6.6 GCal/tcs against the global best of 4.5GCal/tcs for coal-based plants. Its carbon emissions are 2.9 tCO2/tcs, almost double the global best.

The plant withdraws freshwater from Yeleshwaram reservoir, which is connected to the Yeleru tributary of the Godavari. Its per unit water consumption at 3.5 m3/tcs is among the lowest in the country for a BF-BOF plant. However, RINL is in the process of increasing its capacity to 11 MTPA. This will increase the amount of water it draws, increasing the stress on Visakhapatnam city.

The plant’s wastewater is discharged into the sea through Gangavram and Appikonda outlets. This is a major problem because effluents from the outlets do not comply with the standards. Significantly, the plant recycles most of the solid waste it generates. It disposes of 0.24 tonnes/tcs, one of the lowest for a BF-BOF plant. The hazardous waste management is also good as all the waste is recycled in the coke oven.

RINL is one of the few plants that more or less meets ambient air quality norms. But its emissions from processes like sinter plant, blast furnace and SMS are high. The plant has the highest coke oven gas collection rate among Indian plants. This indicates less leakage of toxic gases from coke oven. But again, two of the four coke oven batteries do not comply with leakage emissions norms. But the air quality monitoring is largely satisfactory.

Like most other plants, RINL’S performance on health and safety is poor despite an OSHAS 18001 certification. It does not undertake special health tests for coke oven battery workers. Between 2007 and 2010, 10 workers died in accidents. The plant is certified ISO 14001 and has a full-fledged environment department. It has good green belt development.

People of Appikonda village complain of water pollution from metallurgical wastewater discharge. However, they did not have a problem with solid waste disposal. While the plant has provided people with employment and medical facilities, there are serious issues concerning resettlement and rehabilitation of people evicted from the land acquired for the plant.

| SAIL plants disappoint

Steel-making giant Steel Authority of India (SAIL), with its five integrated units in Bhilai, Bokaro, Durgapur, Burnpur and Rourkela, performed poorly in GRP.

SAIL has more than 35,000 ha under its possession and employs 0.1 million people. It produces nearly one-fifth of the steel the country produces. Being a public sector enterprise, SAIL was expected to proactively take part in GRP. But it did not. Persuasions from the ministry of steel and repeated attempts by GRP failed to convince the company to take part in the project. Later, SAIL Rourkela came forward to participate, but not the others.

To collect information on non-participating plants, GRP filed Right To Information applications. IISCO Burnpur and SAIL Bhilai replied with minimum information.SAIL Durgapur and SAIL Bokaro did not provide even that. GRP surveyors had to collect information from secondary sources.

All the SAIL units use blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) route for steel making. Their overall environmental performance was found to be poor.

Their specific primary energy consumption was 6.5-8.2 Giga calories per tonne crude steel (GCal/tcs) against the global best of 4.5 GCal/tcs. The most energy-efficient SAIL plants—in Durgapur and Bhilai—consumed about 45 per cent higher primary energy than the global best practices. The worst—IISCO, Burnpur—consumed 80 per cent higher.

Similarly, the specific carbon emissions of SAIL plants were 2.9-4.2 tonne carbon per tonne crude steel (tCO2/tcs). For BF-BOF process, the global best practice is 1.7 tCO2/tcs.

SAIL plants were also highly water inefficient. In fact, they were the worst performing plants on water use and efficiency parameters. Their specific water consumption rate is 16-32 m3/tcs. This includes water used for process, captive power plants and township. These plants put very high stress on the rivers by first drawing huge quantities of water and then discharging wastewater into them.

Though SAIL Rourkela did not perform well, it received 1 Leaf Award. The fact that it voluntarily participated indicates its willingness to improve.

|

A growing challenge

Steel sector is only going to grow. So will resource stress and pollution

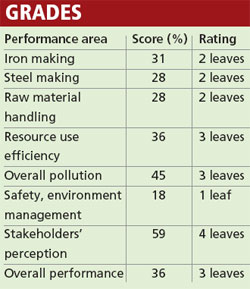

The Iron and steel sector has seen phenomenal growth since economic liberalisation in 1991. A spurt in infrastructure development, housing construction and industrial projects that followed liberalisation has resulted in a growth rate of 8 per cent in the sector. India’s annual steel production has more than doubled to 75 million tonnes in the past decade and is growing at the fastest pace after China.

Unlike world steel production, Indian steel industry has not been significantly influenced by the fluctuations in global economy. In fact, it plans significant expansion. As many as 301 MoUs have been signed between companies and state governments to set up steel plants of an estimated capacity of 488.7 million tonnes per annum. Steel consumption in the country is expected to increase owing to rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and motorisation. If the sector continues to grow at 8 per cent, steel production in India will increase fivefold and reach 325 million tonnes a year by 2030.

This projection throws up tough challenges. As the Green Rating Project shows environmental management of the steel industry is poor. Unless it switches to clean technology and efficient resource management the future growth will have serious repercussions. Following are the major concerns:

• Emissions from dirty route: At present, the industry uses two main routes of steel production: the traditional, relatively energy-efficient BF-BOF route; and the relatively energy-inefficient DRI-EAF route based on coal. The energy-efficient BF-BOF route currently accounts for 49 per cent of the steel production. Production through this route has grown at 5.5 per cent since 1991-92 and this rate is likely to continue till 2030. The DRI-EAF route is projected to grow faster at over 11 per cent a year till 2030-31. This is because of two reasons: one, it is cheaper to set up; two, it mostly uses low-grade, non-coking coal, which is abundantly available in India.

India is the leading producer of coal-based sponge iron. The total production of sponge iron in the country in 2010-11 was reported to be 26.71 million tonnes, of which 78 per cent was through the coal-based route. Growth of the much cleaner gas-based sponge iron production has remained nearly stagnant since gas is expensive and not easily available. This means in the next 20 years, the route for producing steel will change in India. The BF-BOF route is expected to contribute only 30 per cent to production in 2030-31, with coal DRI-EAF contributing the lion’s share of 58 per cent. This is bad for the environment as the coal-based DRI route is highly polluting.

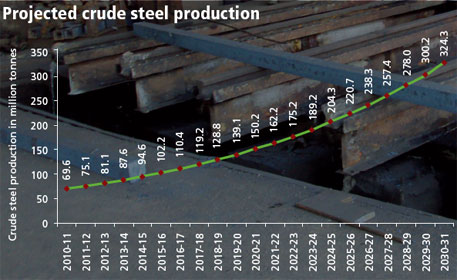

Given that average energy requirement for producing a tonne of primary crude steel (tcs) is 7 giga calories, by 2030-31 the total energy demand of the sector will increase by more than four times, assuming that 20 per cent of crude steel will be coming through steel scrap. Producing this much energy will require 280 million tonnes of coking coal equivalent. With the increase in energy consumption, carbon emissions from the sector are likely to grow fivefold. At present, the sector produces 2.4 tonnes of CO2 for every tonne of crude steel produced.

• Severe water stress: Water consumption for the sector is 11 m3/tcs. But considering the huge size of the industry, the total annual requirement is 700 million m3. This is estimated to rise to 3,400 million m3 by 2030-31, which is 2.5 times the current annual water supply to Delhi. Given that almost all the integrated steel plants are dependent on surface water—even coastal plants are not using sea water and rainwater harvesting is in the nascent stage—this will create immense water stress.

• More land for more production: At present, the steel industry holds a total of about 75,000 hectares (ha) to produce 69.6 million tonnes of steel annually. New plants being set up are more efficient but still use 270 ha per million tonne of steel capacity. At this rate, meeting the projected crude steel production in India by 2020-21 will require about 97,000 ha, and by 2030-31 nearly 0.14 million ha. It means nearly double the land industry holds at present will be required by the steel sector in 2030-31.

• Iron ore crunch: The industry’s iron ore requirement will increase to more than four times (468 million tonnes) by 2030-31, from 111 million tonnes in 2010-11. Indian steel plants are already not getting enough iron ore because nearly half the ore produced in India is exported. In 2010-11, India produced 213 million tonnes of iron ore. Of this, 100 million tonnes was exported.

Whether it is land, water, energy or iron ore, the stress on natural resources is extremely high. How is the industry going to meet its future demand? Pollution will be an additional problem since Indian practices are far behind global standards.

Wastewater release will multiply if the sector does not switch to zero-water discharge, and so will air emission. Solid waste, particularly slag and char from steel melting shops, is already a major problem. The industry will face serious problems unless it adopts global best practices.

Green Rating Team: Umashankar S, Sanjeev Kumar Kanchan and Kanchan Kumar Agarwal. Contributions by Ishikaa Sharma and Sunanda Mehta. GRP is funded by MoEF-UNDP

Roadmap for the future

Scope for the steel industry to improve is tremendous

Author: Chandra Bhushan

The Green Rating Project (GRP) is a great teacher of details and substance. It follows a process that is rigorous, independent, participatory and transparent. This allows it to present a realistic and unbiased assessment, and an achievable roadmap for future.

The project has two key messages for the steel industry. First, there is a tremendous scope for improvement in all areas. Considering the high profits the sector is making, there is no reason steel industry cannot upgrade technology and set up management systems to improve its performance.

The second message is a warning: if the sector does not take quick steps to improve its performance, soon its sheer size will create insurmountable ecological and social problems. Marginal improvement will not help; leapfrog solutions are required. In other words, the industry will have to make steel differently. If Indian steel industry wants to grow without causing social and ecological upheaval, it must take at least these steps:

• Technology innovation to improve energy efficiency and reduce GHG emissions: The Indian steel industry must reduce its specific energy and GHG emissions by half in the next 10-15 years; nothing less will suffice. This can be done by using existing best available technologies as well as by developing new ones. The industry must come together and invest in R&D to leapfrog.

• Lower water consumption: At the current level of efficiency, there will not be enough water to increase production. This will require technologies for recycling and reuse, but most importantly, this will require better accounting, auditing and management systems. Steel plants should close their water cycle and become zero-discharge units. Proper pricing of water will go a long way in making the industry water prudent.

• Recycle and reuse of solid waste: With the existing technology, 90 per cent of the solid waste generated can be easily reused. The remaining should be used in laying roads and in constructing buildings and railway tracks.

• Reduction in air pollution: This can only be done if the steel industry can manage fugitive emissions. This will require it to seal and cover raw material storage and handling operations and capture fugitive emissions from operations. The steel industry can easily meet the stack emissions standard of 20 microgram/Nm3. To eliminate the toxic emissions, only non-recovery coke ovens should be allowed. These should become the regulatory standard.

• Efficient land use: There is an urgent need to rationalise land use in existing plants and set norms for land-use efficiency for new plants. The government must devise policies to efficiently use vacant land in possession of steel plants. Upcoming steel plants must use less than 200 hectares per million tonne installed capacity.

• Improved occupational health and safety performance: Steel plants must put in place effective management systems and invest in health and safety. Contract workers must have the same level of health and safety protection as permanent employees.

• Dialogue and engagement with local stakeholders: The industry needs to improve its relationship with communities. The growing sector will need large tracts of land for setting up plants and opening mines, besides huge quantities of water. This is already leading to conflicts between industry and communities. The steel industry will, therefore, have to devise a mechanism that will treat communities as stakeholders and beneficiaries, rather than alienating them.

• No cheap natural resources: There is a huge difference between companies in terms of the cost of raw material and energy. Companies with captive iron ore and coal mines have a big advantage over others, though they compete in the same market. Evidently, companies with high raw material and energy costs have innovated to improve efficiency and performed better under GRP than those with captive iron ore and coal mines. This indicates that proper raw material pricing is important to improve the efficiency and environmental performance of the sector.

Indian steel industry is poised for a major growth, but this growth should not happen on the back of cheap raw material, energy, water and disregard for the welfare of workers. This would be bad for the economy and for the environment.

Originally published in Down To Earth, URL: http://www.downtoearth.org.in/content/stained-steel?page=0,0

Comments

Post a Comment